Last time we visited this area in Mexico I didn’t get a chance to visit Chichén Itzá so this time I didn’t want to miss the opportunity. It is known as one of the seven wonders of the world.

Chichén Itzá is about a three hour drive from where we are staying so I chose a tour that was leaving early in the morning to beat the crowds and the heat of the day. I had one of those nights sleep that you have when you are catching an early morning flight – I was awake about 2.20am worrying that I would sleep through the alarm and then when I went back to sleep I had some weird dreams. All’s well that ends well – I didn’t sleep through the alarm and made my 5.50am pick up.

We got shuttled to a central meeting point before hopping on a bigger bus to head to Chichén Itzá. Our guide for the day was Marcos who is an archeologist. He did his masters on Chichén Itzá with a focus on proving that there were many other races and cultures on these lands before they were discovered by the Spanish. He spoke Spanish and English and switched between the two with ease as there were both English and Spanish speaking people on the bus. When we got to Chichén Itzá we were split into two groups – English speaking and Spanish speaking so that was good. Marcos lead the English speaking group so that was great. He had warned us about how hot it can get there and he wasn’t wrong. It didn’t feel super hot but I was dripping within minutes.

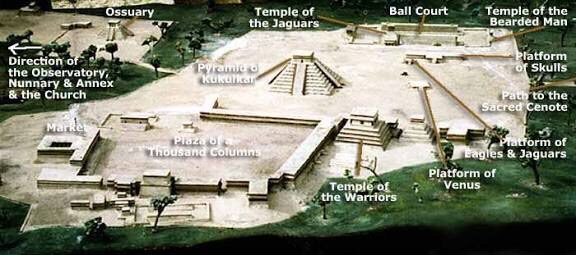

The stepped pyramids, temples, columned arcades, and other stone structures of Chichén Itzá were sacred to the Maya and a sophisticated urban center of their empire from A.D. 750 to 1200.

Marcos described the Mayan people as short with very round heads that sit very close to their shoulders. There are about 3 million Mayan people in a large number of communities around the Yucatan Peninsula. He said to have a look around the hotel where we are staying and you will see lots of them – now that he mentioned it, I understood who he was talking about.

Viewed as a whole, the incredible complex reveals much about the Maya and Toltec vision of the universe—which was intimately tied to what was visible in the dark night skies of the Yucatán Peninsula.

The most recognizable structure here is the Temple of Kukulkan, also known as El Castillo. This glorious step pyramid demonstrates the accuracy and importance of Maya astronomy—and the heavy influence of the Toltecs, who invaded around 1000 and precipitated a merger of the two cultural traditions.

The temple has 365 steps—one for each day of the year. Each of the temple’s four sides has 91 steps, and the top platform makes the 365th.

Devising a 365-day calendar was just one feat of Maya science. Incredibly, twice a year on the spring and autumn equinoxes, a shadow falls on the pyramid in the shape of a serpent. As the sun sets, this shadowy snake descends the steps to eventually join a stone serpent head at the base of the great staircase up the pyramid’s side.

I got my birthdate translated using the Mayan calander – see below for an explanation as to how it works. I think I will be trying to figure it out for the rest of my life!

Marcos talked about all these mathematical wonders and also demonstrated the sounds that could be heard by clapping your hands while standing in different positions around the Temple. It was quite incredible – it sounded distinctly like a bird chirping as it reverberated off all the structures. One clap caused 7 echoes – the number 7 having some significance I relation to the practice of Reiki which uses 7 prongs to massage the head.

The Mayan’s worshipped the rattle snake because it shed it’s skin every 260 days symbolising the continuation of life. Interestingly the Tzolkin calendar described below has 260 days.

The number 9 symbolises Men – multiply anything by the number 9 and then add up the result and it will equal 9. The number nine represents the sun.

The number 13 represents Women – 365 days in a year divided by 28 days in a women’s cycle equals 13. The number thirteen represents the moon – there are 13 full moons each year.

The Maya’s astronomical skills were so advanced they could even predict solar eclipses, and an impressive and sophisticated observatory structure remains on the site today.

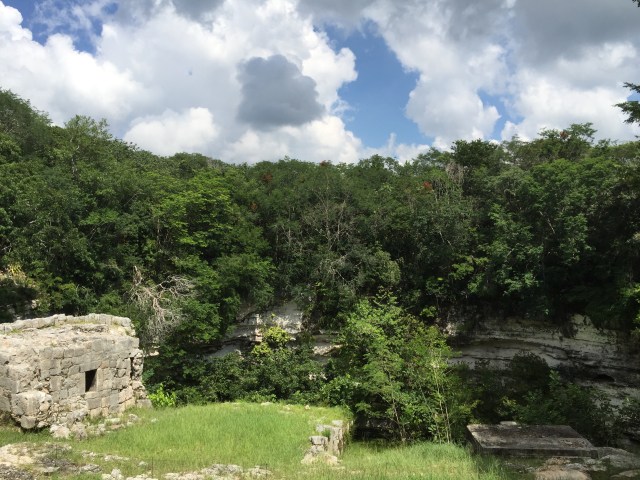

This great city’s only permanent water source was a series of sinkhole wells. Spanish records report that young female victims were thrown into the largest of these, live, as sacrifices to the Maya rain god thought to live in its depths. Archaeologists have since found their bones, as well as the jewelry and other precious objects they wore in their final hours.

Chichén Itzá’s ball court is the largest known in the Americas, measuring 554 feet (168 meters) long and 231 feet (70 meters) wide. During ritual games here, players tried to hit a 12-pound (5.4-kilogram) rubber ball through stone scoring hoops set high on the court walls. Competition must have been fierce indeed—losers were put to death.

In the ball court, Marcos made one of our group, Andrew, walk down to the other end and when he got to the little stone pillar he was to turn around and measure three steps back towards us and stand there. Marcos then called his name in a normal tone – he didn’t shout. Andrew was to raise his hand when he heard his name – on the second go, he raised his hand. He was standing about 165 metres away so that was quite amazing. The King used to sit at the end where Andrew was to watch the games – the visitors used to sit where we were. Apparently this sound travel phenomena only worked one way – the King could hear the visitors but they couldn’t hear him. Good strategy.

The other thing that Marcos believed was that the winning captain actually got sacrificed not the losing one as the information above says. He believed it was an honour to die and supported the Mayan’s beliefs about offering sacrifices for the continuation of human life.

Chichén Itzá was more than a religious and ceremonial site. It was also a sophisticated urban center and hub of regional trade. But after centuries of prosperity and absorbing influxes of other cultures like the Toltecs, the city met a mysterious end.

During the 1400s people abandoned Chichén Itzá to the jungle. Though they left behind amazing works of architecture and art, the city’s inhabitants left no known record of why they abandoned their homes. Scientists speculate that droughts, exhausted soils, and royal quests for conquest and treasure may have contributed to Chichén Itzá’s downfall.

Recently this World Heritage site was accorded another honor. In a worldwide vote Chichén Itzá was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World.

The New Seven Wonders of the World were announced on July 7th, 2007 in Lisbon, Portugal after seven years of publicity and promotion.

* Chichen Itza, Mexico

* The Great Wall, China

* Petra, Jordan

* Christ Redeemer, Brazil

* Machu Picchu, Peru

* The Roman Collesseum, Italy

* The Taj Mahal, India

From its abandonment during the 15th century, Chichén Itzá underwent a process of gradual deterioration until the first excavations at the site began more than a century ago. Nevertheless, the excellent materials and building techniques used by the Maya in the construction of the buildings secured that the architectonic, sculptural and pictorial essence of Chichén Itzá would be conserved through the centuries.

Chichén Itzá is protected by the 1972 Federal Law on Monuments and Archaeological, Artistic and Historic Zones and was declared an archaeological monument by a presidential decree in 1986.

The site remains open to the public 365 days of the year, and received a minimum of 3.500 tourists per day, a number which can reach 8.000 daily visitors in the high season. This means that the site needs constant maintenance and attention in order to avoid deterioration of its prehispanic fabric.

Yucatan is the only state in Mexico where two institutions are involved in the management of archaeological sites: the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), which is in charge of the care and conservation of the archaeological site, and the Board of Units of Cultural and Tourism Services of the State of Yucatan.

The Maya Calendar

The Maya calendar is a system of three interlacing calendars and almanacs which was used by several cultures in Central America, most famously the Maya civilization.

The calendar dates back to at least the 5th century BCE (Before Common Era) and is still in use in a few Mayan communities today. The Mayan calendar moves in cycles with the last cycle ending in December 2012. This has often been interpreted as the world will end on 21 December 2012, at 11:11 UTC.

Doomsday Prophecies

The last day of the Mayan calendar corresponds with the December Solstice, which has played a significant role in many cultures all over the world.

Not a Maya Invention

The Maya didn’t invent the calendar, it was used by most cultures in pre-Columbian Central America – including the Maya – from around 2000 BCE to the 16th century. The Mayan civilization developed the calendar further and it’s still in use in some Maya communities today.

Wheels Working Together

The Mayan Calendar consists of three separate corresponding calendars, the Long Count, the Tzolkin (divine calendar) and the Haab (civil calendar). Time is cyclical in the calendars and a set number of days must occur before a new cycle can begin.

The three calendars are used simultaneously. The Tzolkin and the Haab identify and name the days, but not the years. The Long Count date comes first, then the Tzolkin date and last the Haab date. A typical Mayan date would read: 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 8 Kumku, where 13.0.0.0.0 is the Long Count date, 4 Ahau is the Tzolkin date and 8 Kumku is the Haab date.

The Haab

The Haab is a 365 day solar calendar which is divided into 18 months of 20 days each and one month which is only 5 days long (Uayeb). The calendar has an outer ring of Mayan glyphs (pictures) which represent each of the 19 months. Each day is represented by a number in the month followed by the name of the month. Each glyph represents a personality associated with the month.

The Haab is somewhat inaccurate as it is exactly 365 days long. An actual tropical or solar year is 365.2422 days long. In today’s Gregorian calendar we adjust for this discrepancy by making almost every fourth year a leap year by adding an extra day – a leap day – on the 29th of February.

The Tzolkin

The divine calendar is also known as the Sacred Round or the Tzolkin which means “the distribution of the days”. It is a 260-day calendar, with 20 periods of 13 days used to determine the time of religious and ceremonial events. Each day is numbered from one to thirteen, and then repeated. The day is also given a name (glyph) from a sequence of 20 day names. The calendar repeats itself after each cycle.

The Long Count

The Long Count is an astronomical calendar which was used to track longer periods of time, what the Maya called the “universal cycle”. Each such cycle is calculated to be 2,880,000 days (about 7885 solar years). The Mayans believed that the universe is destroyed and then recreated at the start of each universal cycle. This belief still inspires a myriad of prophesies about the end of the world.

The “creation date” for the current cycle we are in today, is 4 Ahaw, 8 Kumku. According to the most common conversion, this date is equivalent to August 11, 3114 BCE in the Gregorian calendar or September 6 in the Julian calendar.

How to Set the Date

A date in the Maya calendar is specified by its position in both the Tzolkin and the Haab calendars which aligns the Sacred Round with the Vague Year creating the joint cycle called the Calendar Round, represented by two wheels rotating in different directions. The Calendar round cycle takes approximately 52 years to complete.

The smallest wheel consists of 260 teeth with each one having the name of the days of the Tzolkin. The larger wheel consists of 365 teeth and has the name of each of the positions of the Haab year. As both wheels rotate, the name of the Tzolkin day corresponds to each Haab position.

The date is identified by counting the number of days from the “creation date”.

A typical long count date has the following format: Baktun.Katun.Tun.Uinal.Kin.

Kin = 1 Day.

Uinal = 20 kin = 20 days.

Tun = 18 uinal = 360 days.

Katun = 20 tun = 360 uinal = 7,200 days.

Baktun = 20 katun = 400 tun = 7,200 uinal = 144,000 days.

The kin, tun and katun are numbered from zero to 19; the uinal are numbered from zero to 17; and the baktun are numbered from one to 13. The Long Count has a cycle of 13 baktuns, which will be completed 1.872.000 days (13 baktuns) after 0.0.0.0.0. This period equals 5125.36 years and is referred to as the “Great Cycle” of the Long Count.

End of the World?

Will the world will end on 21 December 2012, at 11:11 UTC?

The Mayan calendar completes its current “Great Cycle” of the Long Count on the 13th baktun, on 13.0.0.0.0. Using the most common conversion to our modern calendar (the Gregorian calendar) the end of the “Great Cycle” corresponds to 11:11 Universal Time (UTC), December 21, 2012, hence the myriad of doomsday prophecies surrounding this date.

Mayan Culture Today

The Maya kept historical records such as civil events and their calendric and astronomical knowledge. They maintain a distinctive set of traditions and beliefs due to the combination of pre-Columbian and post-Conquest ideas and cultures. The Maya and their descendants still form sizable populations that include regions encompassing present day Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador and parts of Mexico.

The Platform of Venus – this is a square shaped platform with steps on all four sides, each with balustrades ending in serpent heads, and whose bodies are represented in the upper section as being plumed and sinuous in form, and combined with fish figures. Mythical creatures, (a combination of jaguar, eagle, serpent and human forms), adorn the center of the side panels. In each corner, there are glyphs associated with the planet Venus. Owing to its position within the plaza, it was probably used for ceremonial purposes.

The Platform of Venus – this is a square shaped platform with steps on all four sides, each with balustrades ending in serpent heads, and whose bodies are represented in the upper section as being plumed and sinuous in form, and combined with fish figures. Mythical creatures, (a combination of jaguar, eagle, serpent and human forms), adorn the center of the side panels. In each corner, there are glyphs associated with the planet Venus. Owing to its position within the plaza, it was probably used for ceremonial purposes.

Tzompantli is called The Wall of Skulls, which is actually an Aztec name for this kind of structure, because the first one seen by the horrified Spanish was at the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan. The Tzompantli structure at Chichen Itza is very interesting Toltec structure, where the heads of sacrificial victims were placed; although it was one of three platforms in the Great Plaza, it was according to Bishop Landa, the only one for this purpose the others were for farces and comedies, showing the Itza’s were all about fun. The platform walls of the Tzompantli have carved beautiful reliefs of four different subjects. The primary subject is the skull rack itself; others show a scene with a human sacrifice; eagles eating all human hearts; and skeletonized warriors with arrows and shields.

Tzompantli is called The Wall of Skulls, which is actually an Aztec name for this kind of structure, because the first one seen by the horrified Spanish was at the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan. The Tzompantli structure at Chichen Itza is very interesting Toltec structure, where the heads of sacrificial victims were placed; although it was one of three platforms in the Great Plaza, it was according to Bishop Landa, the only one for this purpose the others were for farces and comedies, showing the Itza’s were all about fun. The platform walls of the Tzompantli have carved beautiful reliefs of four different subjects. The primary subject is the skull rack itself; others show a scene with a human sacrifice; eagles eating all human hearts; and skeletonized warriors with arrows and shields.

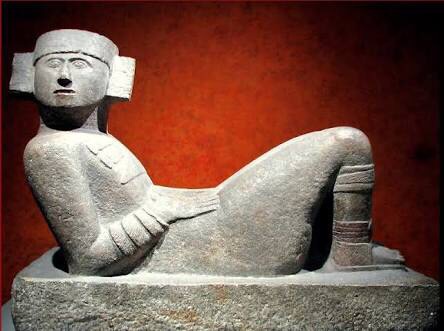

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichen Itza, however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid’s summit (and leading towards the entrance of the pyramid’s temple) is a Chac Mool.

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichen Itza, however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid’s summit (and leading towards the entrance of the pyramid’s temple) is a Chac Mool.

A Chac Mool is the term used to refer to a particular form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach.

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns, although when the city was inhabited these would have supported an extensive roof system where they would have held a market for trading various goods.

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns, although when the city was inhabited these would have supported an extensive roof system where they would have held a market for trading various goods.

The Temple of the Jaguars is attached to the Great Ball Court

The Temple of the Jaguars is attached to the Great Ball Court

Love that blog. Sent to Boff too

Pingback: 8.SUMMER SOLSTICE: Chichén Itzá | C I T I N E R A R I E S